Image 1 of 9

Image 1 of 9

Image 2 of 9

Image 2 of 9

Image 3 of 9

Image 3 of 9

Image 4 of 9

Image 4 of 9

Image 5 of 9

Image 5 of 9

Image 6 of 9

Image 6 of 9

Image 7 of 9

Image 7 of 9

Image 8 of 9

Image 8 of 9

Image 9 of 9

Image 9 of 9

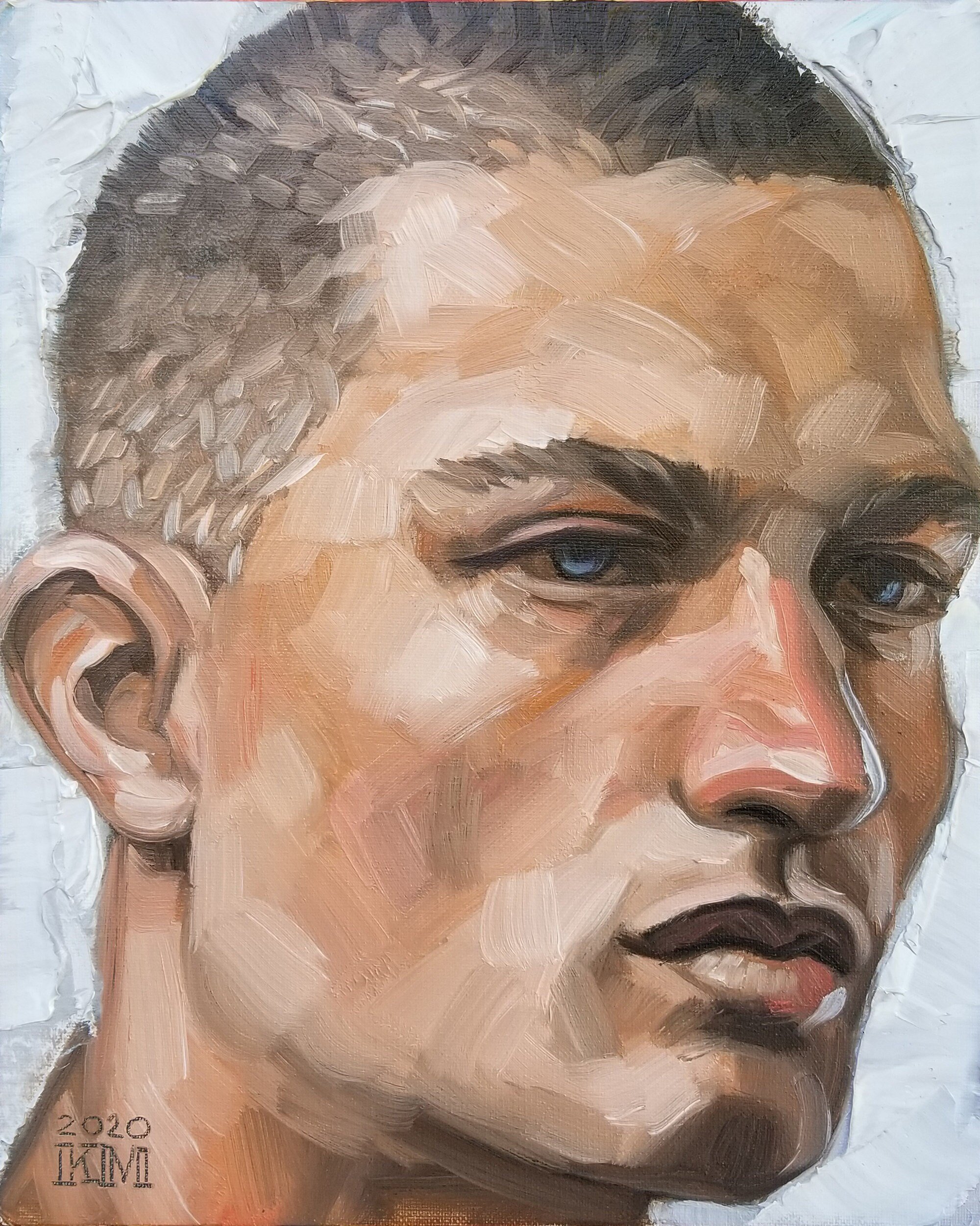

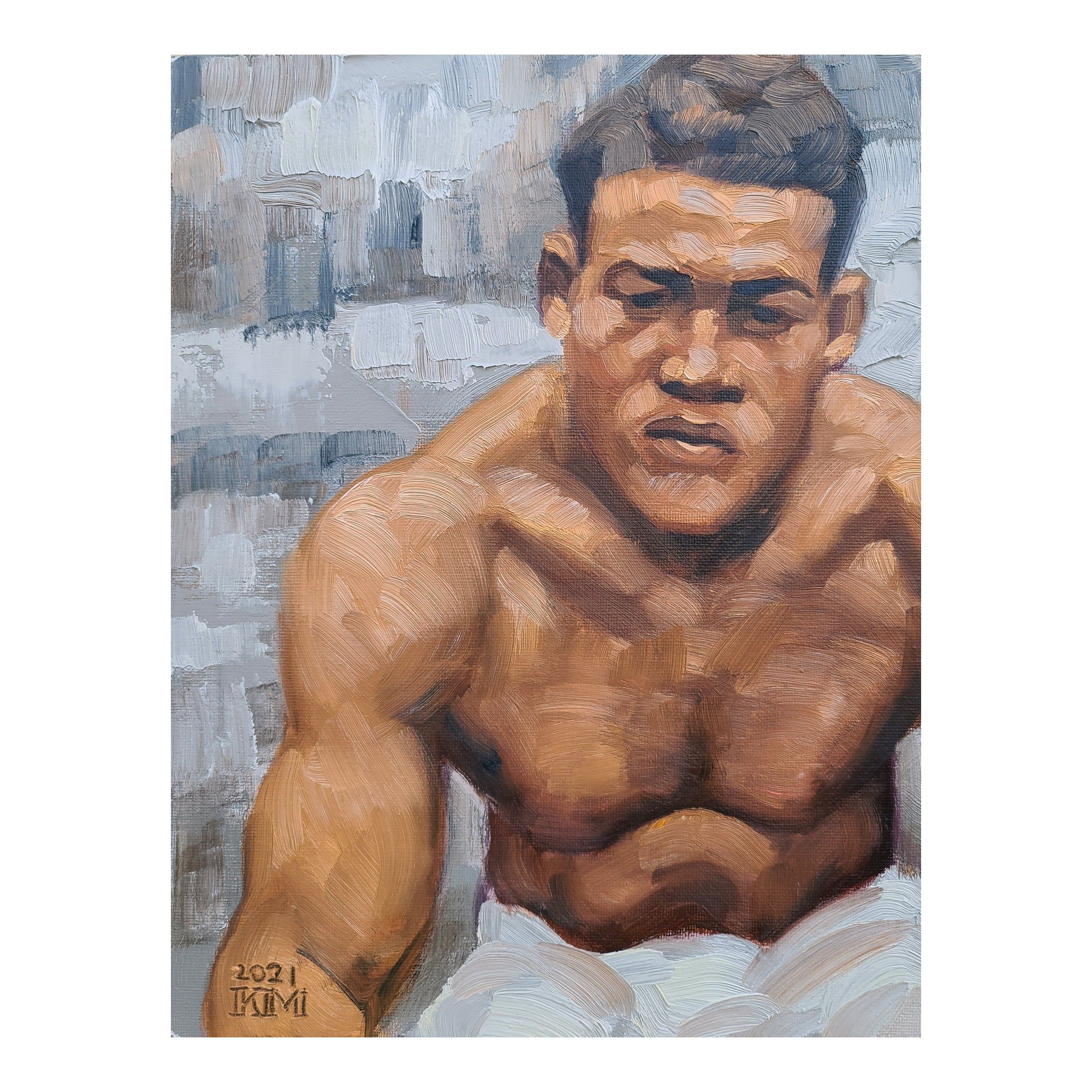

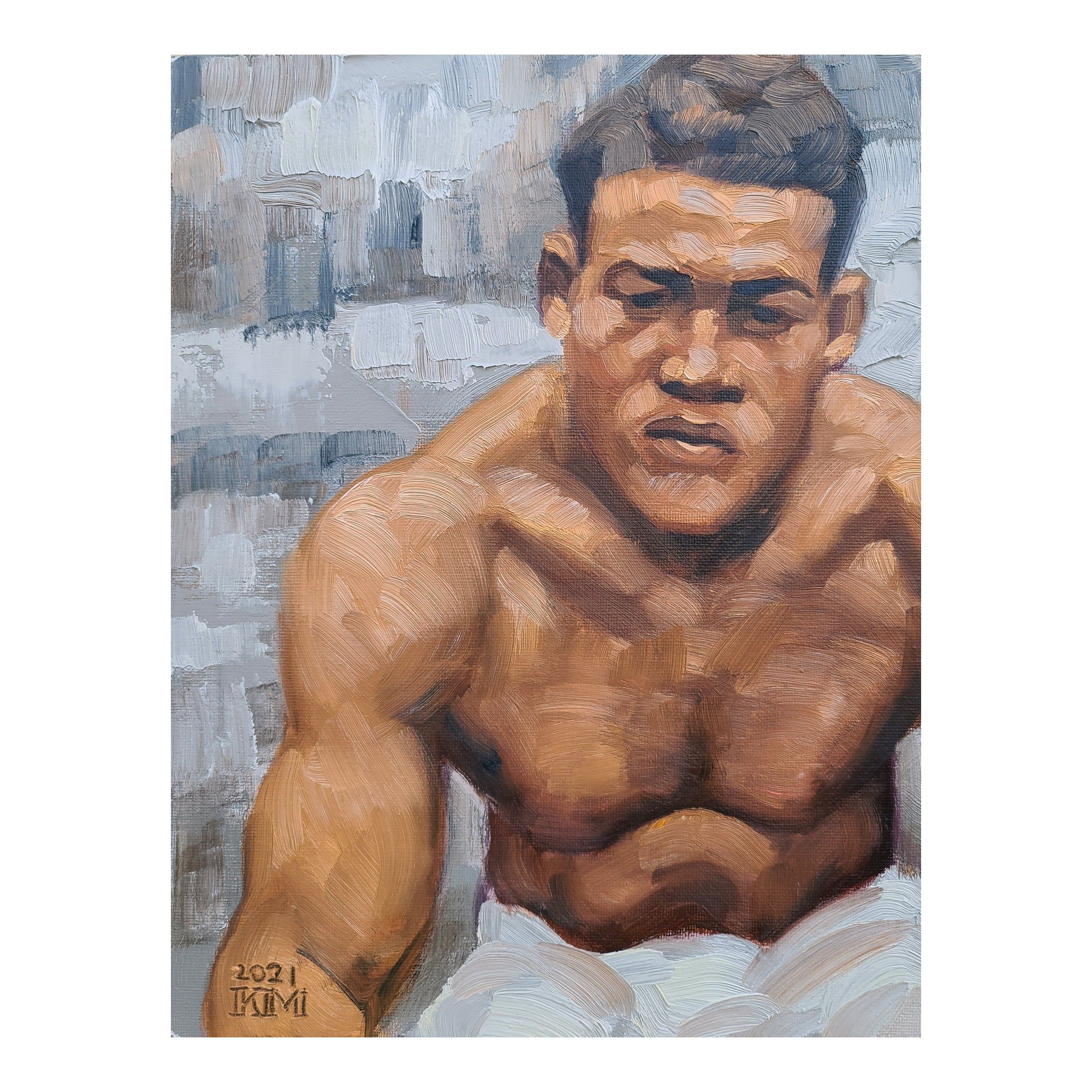

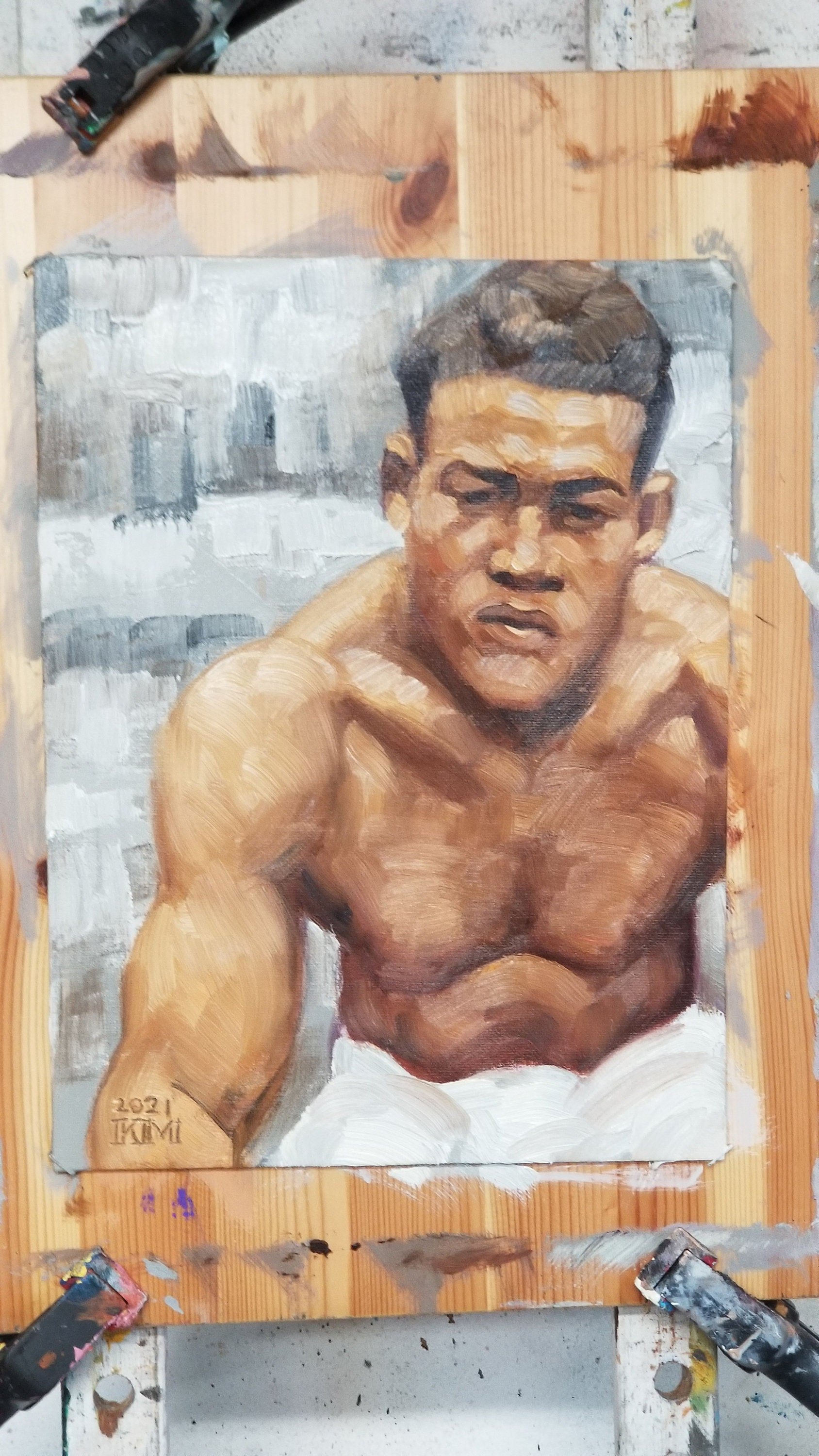

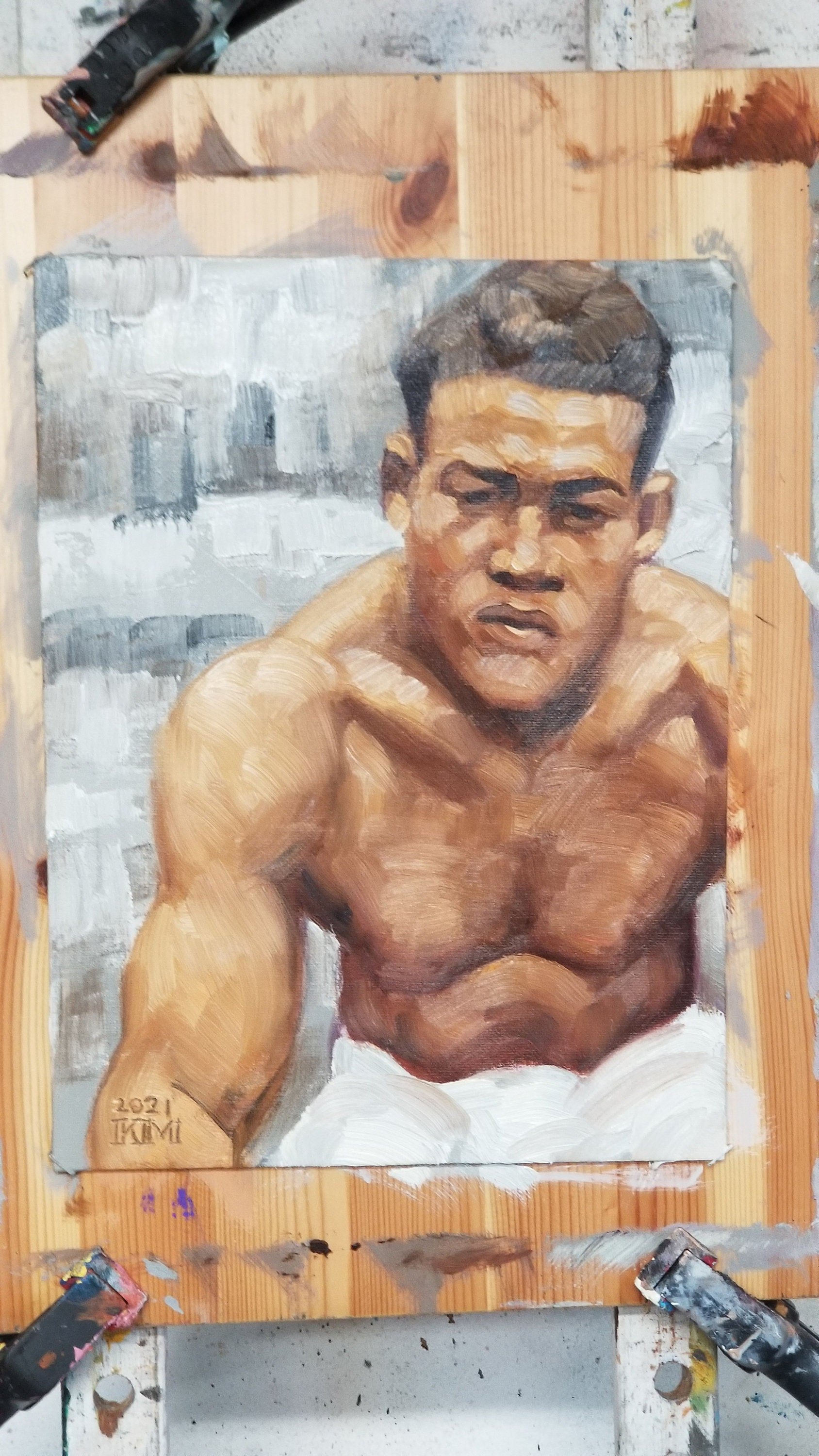

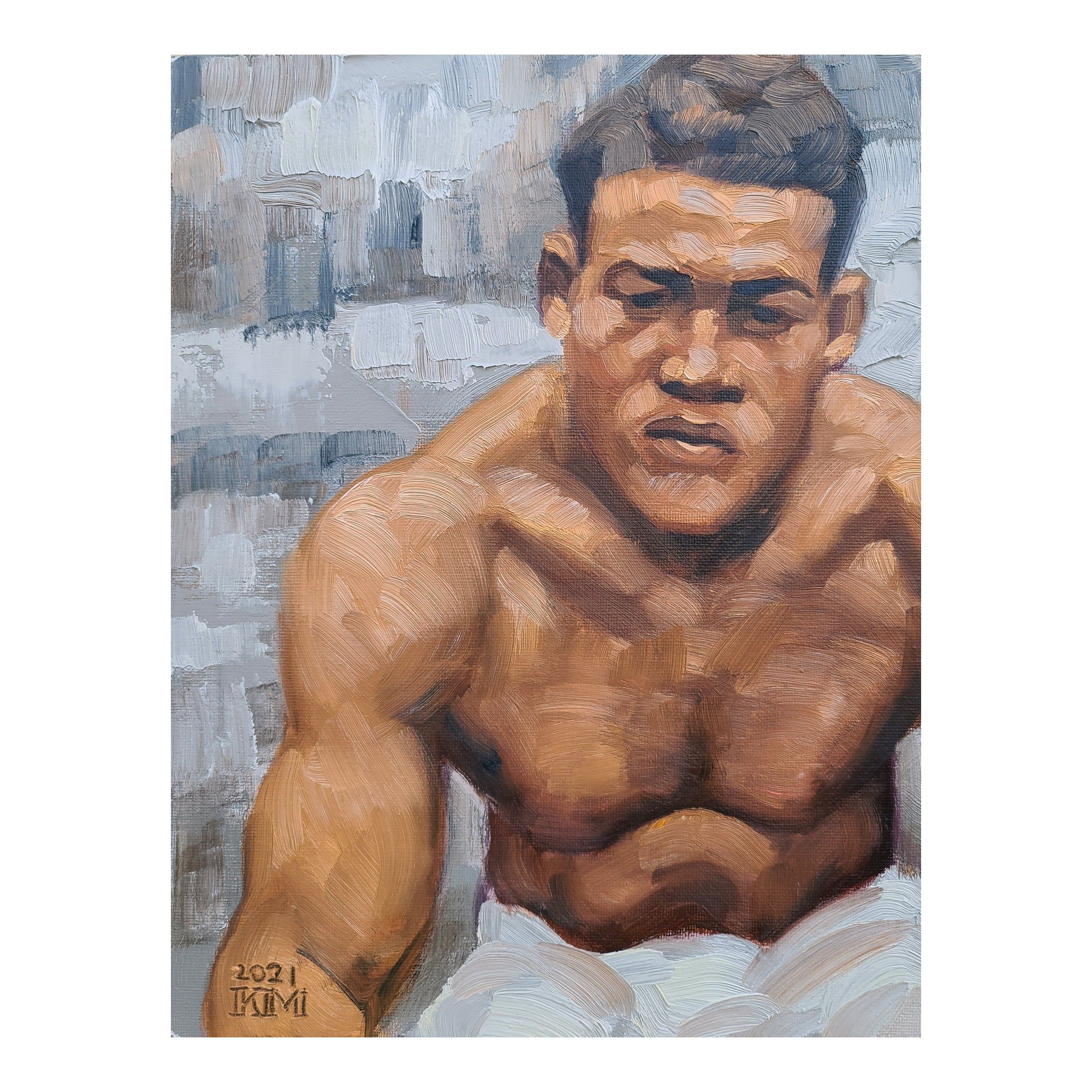

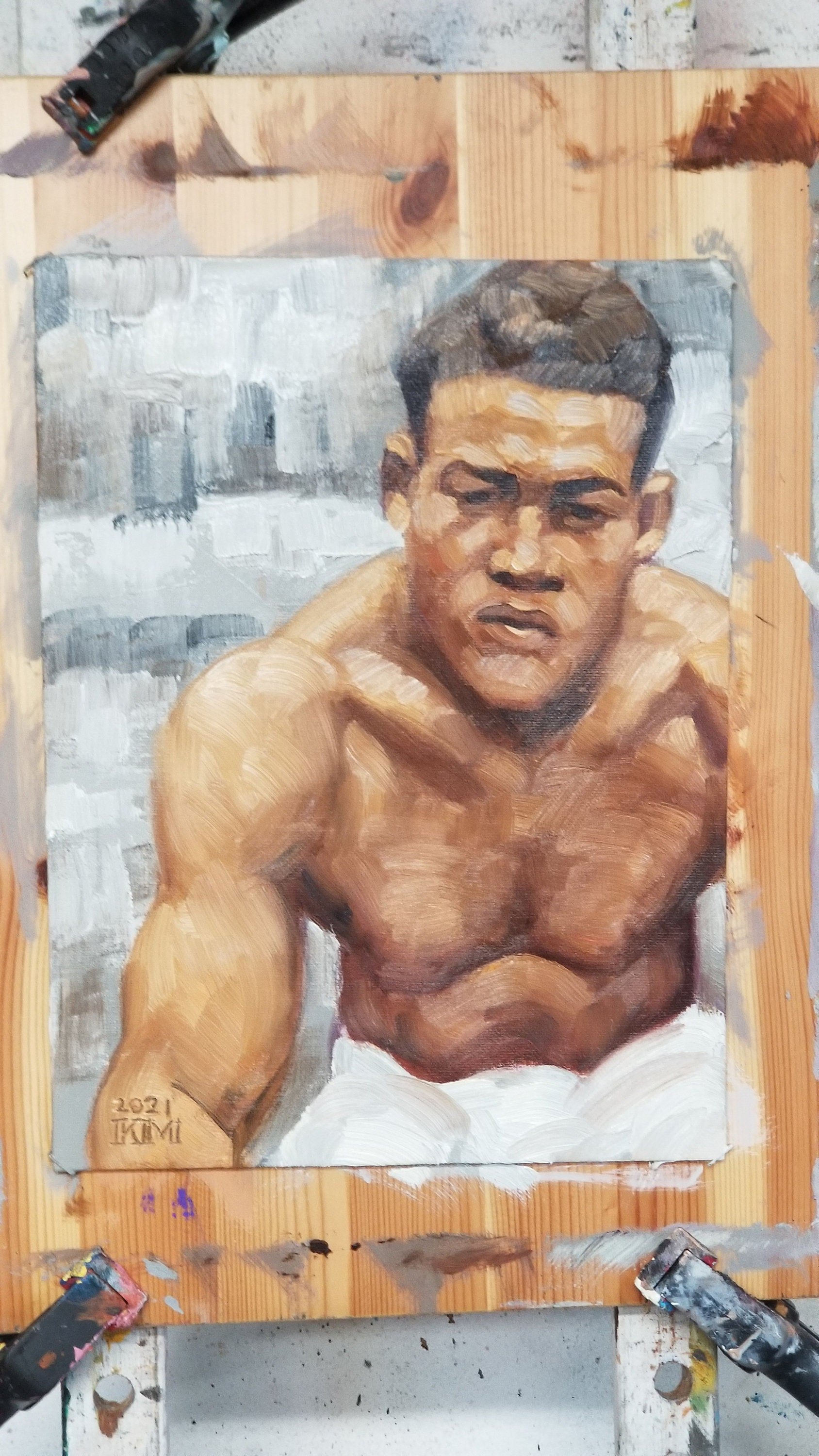

Joe Louis, The Brown Bomber, 9x12 inches oil paint on canvas panel by Kenney Mencher

$275.00

Sold Out

FREE SHIPPING

THIS WORK IS ORIGINAL (NOT A PRINT OR GICLEE)

Shipping takes 3-4 Weeks

Joseph Louis Barrow was an American professional boxer who competed from 1934 to 1951. Nicknamed the Brown Bomber, Louis is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential boxers of all time. He reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1937 until his temporary retirement in 1949

Quotes from Joe Louis

“Every man's got to figure to get beat sometime.” “I don't like money, actually, but it quiets my nerves.” “Everybody wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die.” ” Once that bell rings you're on your own.

How Joe Louis became a symbol of the fight against racism

June 27, 2014 12:37 PM CDT BY JOHN WIGHT

On June 19, 1936 the Brown Bomber Joe Louis climbed through the ropes at the Yankee Stadium in New York to face German heavyweight contender Max Schmeling in front of a sell-out crowd to contest a non-title bout scheduled for 15 rounds.

Louis was just 22 when he faced Schmeling for the first time, undefeated in 24 fights. Schmeling had already won and lost the world title and at 30 was felt to be easy pickings for his much younger and more complete opponent, who was already on the way to establishing the legend he was destined to become.

The backdrop: fascism in Europe, lynchings in U.S

The onward march of fascism in Europe was the backdrop to the fight. Adolf Hitler had been in power in Germany for three years, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was intent on reliving the glory days of the Roman empire and Spain was embroiled in a brutal civil war which foreshadowed the cataclysm that was to engulf Europe and the world just a few years later.

Meanwhile, the United States regarded itself as the home of freedom and democracy, even though for young black men like Joe Louis it was closer to hell, with lynchings still a regular occurrence in parts of the south and blacks treated as second-class citizens even in areas without formal segregation.

The fight itself proved that Schmeling’s claim to have identified a flaw in the Brown Bomber’s style was not mere hyperbole. Louis had a habit of lowering his left hand after jabbing with it, which Schmeling aimed to exploit with right hands.

The German dropped Louis to the canvas for the first time in his career with just such a right hand in the fourth round and by the time he finally knocked him out in the 12th he was ahead on all three of the judges’ scorecards.

It was a major upset. In black communities throughout the US Louis’ first defeat was met with huge consternation by people who saw in him their savior and hope.

Maya Angelou wrote: “My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, yet another Black man hanging on a tree. One more woman ambushed and raped. A Black boy whipped and maimed. It was hounds on the trail of a man running through slimy swamps. … If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help.”

Meanwhile, after a personal message from Hitler congratulating him, Schmeling told a German reporter: “At this moment I have to tell Germany, I have to report to the Fuhrer in particular, that the thoughts of all my countrymen were with me in this fight.

“That the Fuhrer and his faithful people were thinking of me. This thought gave me the strength to succeed in this fight. It gave me the courage and the endurance to win this victory for Germany’s colors.”

The second fight: Schmeling and Louis political symbols

By the time of the second fight two years later, the world lay on the brink of war and the Nazis’ terror campaign against communists, socialists, trade unionists, the disabled, gays, Gypsies and Jews was underway.

Schmeling and Louis were now political symbols for their respective countries whether they liked it or not and, as the fight on June 22 1938 approached, again held at New York’s Yankee Stadium, the tension far exceeded any that had been present in the lead-up to the first contest.

Despite his message praising Hitler following the first fight Schmeling was not a member of the Nazi party and always denied Nazi claims of racial superiority.

His wife and mother were prevented from travelling to the US with him to forestall the possibility of them defecting. His entourage included a Nazi official to handle press and publicity.

It was this official who was responsible for issuing the infamous statement that a black man could not defeat Schmeling and that his purse would be used to help pay for more German tanks.

As for Louis, he attended a meeting with President Franklin D Roosevelt at the White House prior to the fight, where he was left in no doubt of the importance of the outcome to the country at large.

The irony was striking

The irony was striking – a young black man whose people were being systematically denied their civil and human rights had become the champion of the country responsible.

Louis was a different fighter to two years earlier. Since losing to the German in 1936 he’d gone on to win the world heavyweight title and successfully defended it three times.

He was 25 and fully in his prime, which told from the opening bell when he went straight on the offensive, unleashing crunching combinations against Schmeling’s body and head.

The German had no answer to the barrage and went down after just 90 seconds. When the action resumed, Louis picked up where he’d left off, again sending his opponent to the canvas.

This time Schmeling’s corner, realizing their man was being taken apart, intervened to call a halt to what by now was a public execution. The fight was over in the first round, causing the 70,000 people crammed into the stadium to go wild.

Perhaps the most famous line in the history of boxing was coined in the aftermath by the leading sportswriter of the day, Jimmy Cannon, who described Louis as “a credit to his race – the human race.”

The victory propelled Louis to fame and celebrity, though he was studious in not displaying any of the defiance or controversy that typified the career of his black predecessor Jack Johnson.

He knew his role and performed it to the letter, serving in the forces in World War II, in which his fame was exploited by the government in the war effort. He ended up broke as a greeter in a Las Vegas casino in his twilight years and died in 1981.

Schmeling donated money to pay for the funeral and also acted as a pallbearer, testimony to the respect and friendship both men went on to enjoy after sharing the ring together.

Schmeling returned to Germany after the fight to find his status had plummeted. The Nazis no longer treated him as a national hero or symbol of Aryan manhood – no great disappointment to the reluctant Schmeling. Indeed, the German champion provided sanctuary to two Jewish boys later the same year during the Kristallnacht pogrom against the Jews. After the war, during which he was conscripted to serve as a paratrooper, Schmeling embarked on a career in business. He died in 2005 just shy of his 100th birthday.

Louis, as with Mohammed Ali in later years, was more than just a boxer to his people. He was a symbol of pride, strength and dignity in the face of the oppression they suffered in the land of the free. Martin Luther King later described what Louis meant to them when he wrote about the execution of a young black prisoner in a southern prison. As the poison gas pellets were dropped in the death chamber and the gas swirled upwards, his last words were: “Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis…”

Reposted from MorningStar.

Warning these are the only sites authorized to sell my art:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/kmencher

https://www.kenney-mencher.net/

http://kenney-mencher.com/

The size is a standard US frame size and can be framed inexpensively.

(Buy framing kits on the US version of Etsy, Amazon or go to DickBlick. (.com's)

I was born in Brooklyn February of 1965. During much of my childhood I lived in Brooklyn, the Bronx, upstate NY, Sarasota, Florida and Manhattan. (Both my mother and father divorced and remarried.) The real hero of my childhood is my older brother Marc who literally changed my diapers, acted as my protector and as my role model.

I started to learn to paint and draw when I was six or seven years old and was convinced that I would be an artist from that age on.

As a teen at the High School of Art and Design I got my best training in Irwin Greenberg’s class where he taught me how to draw, oil paint and watercolor. I also attended classes at the Cooper Union and Art Students League.

My parents threw me out in my senior year of high school, so I earned my GED and worked construction on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was a rough time but my older brother and his partner Kirk rescued me by inviting me to move with them to Cincinnati, Ohio to live and study. While a college student, I worked in restaurants and painted as much as I could. After a year at the University of Cincinnati, I went back to the Bronx where I finished college at CUNY Lehman. Lehman is a fantastic college.

After completing my undergraduate studies, I lived in California and then Ohio completing my two masters’ degrees in Art History and Studio Art. After school I was lucky enough to have dual careers as an exhibiting artist and tenured professor.

In 2014 I began to work on paintings with a strong homoerotic content. Despite excellent sales and well received shows, the galleries I worked with wouldn’t show my new queer work, so I’ve been successfully working mainly directly with my collectors. This change has freed me and allowed me to focus on themes and subjects that, in the past, were rejected or resulted in censorship.

Things are going great! In 2016, after eighteen years of teaching art history and studio courses, I resigned a tenured professorship to pursue painting full time.

EDUCATION

1993-1995 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

MFA Painting

1991-1994 University of California, Davis, CA

MA Art History

1988-1991 City University of New York, Bronx, NY

Magna Cum Laude; BA Art History

1988 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

1981-1985 Art Students' League, Manhattan, NY

1978-1982 Art & Design High School, Manhattan, NY

EMPLOYMENT

1999-2016 Associate Professor of Art & Art History, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

1998-1999 Instructor of Art History & Western Civilization, San Francisco University High School

1996-1998 Assistant Professor of Art & Art History, Texas A&M University, Laredo, TX

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2021 Lone Star Saloon, San Francisco, CA

It’s All About the Bears

2016 Tracy Center for the Arts, Tracy, CA

The Convict and the Boy, A Graphic Novel and Installation by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Art Museum of Los Gatos, Los Gatos, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2008 Sequential Art Gallery, Portland, OR

Cads and Coquettes

2008 Varnish Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

Lovers and Liars

2007 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Faces and Farces

2007 Gallery 2611, Redwood City, CA

Clichés and Characters

2006 Klaudia Marr Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

Kenney Mencher: Recent Work

2006 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Apperceptions and Allegories

2006 Norton Studio Gallery, Pacific Art League, Palo Alto, CA

Being There

2006 Esteban Sabar Gallery, Oakland, CA

Similes and Sayings

2005 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Hamlettes on Wry

2005 Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts, Mountain View, CA

2004 Louie-Meager Art Gallery, Gary Soren Smith Center, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Dress Code

2004 STRS Gallery, Sacramento, CA

1997 Laredo Center for the Arts, Laredo, TX

Noir Images (Solo Show)

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

The Men's Room

2010 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Go Figure

2010 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Resurgence

2009 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

In Black and White: Monochromatic Paintings by Kenney Mencher and Caroline Meyer

2008 Art Museum of Los Gatos, CA

Sex, Politics and Misogyny, Peter Langenbach and Kenney Mencher

2006-07 Klaudia Marr, Santa Fe, NM

14th Annual Realism Invitational

13th Annual Realism Invitational

2006 Triton Art Museum, Santa Clara, CA

Beyond the Likeness: Self Portraits by California Artists

2003 Hang Gallery Palo Alto, CA

One More Thing Before I Go

1999 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

First Annual Realism Invitational

2001 Craighead-Green, Dallas, TX

Kenney Mencher and Connie Connally

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Small Works

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Nancy Switzer, Milt Kobayashi, and Kenney Mencher

THIS WORK IS ORIGINAL (NOT A PRINT OR GICLEE)

Shipping takes 3-4 Weeks

Joseph Louis Barrow was an American professional boxer who competed from 1934 to 1951. Nicknamed the Brown Bomber, Louis is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential boxers of all time. He reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1937 until his temporary retirement in 1949

Quotes from Joe Louis

“Every man's got to figure to get beat sometime.” “I don't like money, actually, but it quiets my nerves.” “Everybody wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die.” ” Once that bell rings you're on your own.

How Joe Louis became a symbol of the fight against racism

June 27, 2014 12:37 PM CDT BY JOHN WIGHT

On June 19, 1936 the Brown Bomber Joe Louis climbed through the ropes at the Yankee Stadium in New York to face German heavyweight contender Max Schmeling in front of a sell-out crowd to contest a non-title bout scheduled for 15 rounds.

Louis was just 22 when he faced Schmeling for the first time, undefeated in 24 fights. Schmeling had already won and lost the world title and at 30 was felt to be easy pickings for his much younger and more complete opponent, who was already on the way to establishing the legend he was destined to become.

The backdrop: fascism in Europe, lynchings in U.S

The onward march of fascism in Europe was the backdrop to the fight. Adolf Hitler had been in power in Germany for three years, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was intent on reliving the glory days of the Roman empire and Spain was embroiled in a brutal civil war which foreshadowed the cataclysm that was to engulf Europe and the world just a few years later.

Meanwhile, the United States regarded itself as the home of freedom and democracy, even though for young black men like Joe Louis it was closer to hell, with lynchings still a regular occurrence in parts of the south and blacks treated as second-class citizens even in areas without formal segregation.

The fight itself proved that Schmeling’s claim to have identified a flaw in the Brown Bomber’s style was not mere hyperbole. Louis had a habit of lowering his left hand after jabbing with it, which Schmeling aimed to exploit with right hands.

The German dropped Louis to the canvas for the first time in his career with just such a right hand in the fourth round and by the time he finally knocked him out in the 12th he was ahead on all three of the judges’ scorecards.

It was a major upset. In black communities throughout the US Louis’ first defeat was met with huge consternation by people who saw in him their savior and hope.

Maya Angelou wrote: “My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, yet another Black man hanging on a tree. One more woman ambushed and raped. A Black boy whipped and maimed. It was hounds on the trail of a man running through slimy swamps. … If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help.”

Meanwhile, after a personal message from Hitler congratulating him, Schmeling told a German reporter: “At this moment I have to tell Germany, I have to report to the Fuhrer in particular, that the thoughts of all my countrymen were with me in this fight.

“That the Fuhrer and his faithful people were thinking of me. This thought gave me the strength to succeed in this fight. It gave me the courage and the endurance to win this victory for Germany’s colors.”

The second fight: Schmeling and Louis political symbols

By the time of the second fight two years later, the world lay on the brink of war and the Nazis’ terror campaign against communists, socialists, trade unionists, the disabled, gays, Gypsies and Jews was underway.

Schmeling and Louis were now political symbols for their respective countries whether they liked it or not and, as the fight on June 22 1938 approached, again held at New York’s Yankee Stadium, the tension far exceeded any that had been present in the lead-up to the first contest.

Despite his message praising Hitler following the first fight Schmeling was not a member of the Nazi party and always denied Nazi claims of racial superiority.

His wife and mother were prevented from travelling to the US with him to forestall the possibility of them defecting. His entourage included a Nazi official to handle press and publicity.

It was this official who was responsible for issuing the infamous statement that a black man could not defeat Schmeling and that his purse would be used to help pay for more German tanks.

As for Louis, he attended a meeting with President Franklin D Roosevelt at the White House prior to the fight, where he was left in no doubt of the importance of the outcome to the country at large.

The irony was striking

The irony was striking – a young black man whose people were being systematically denied their civil and human rights had become the champion of the country responsible.

Louis was a different fighter to two years earlier. Since losing to the German in 1936 he’d gone on to win the world heavyweight title and successfully defended it three times.

He was 25 and fully in his prime, which told from the opening bell when he went straight on the offensive, unleashing crunching combinations against Schmeling’s body and head.

The German had no answer to the barrage and went down after just 90 seconds. When the action resumed, Louis picked up where he’d left off, again sending his opponent to the canvas.

This time Schmeling’s corner, realizing their man was being taken apart, intervened to call a halt to what by now was a public execution. The fight was over in the first round, causing the 70,000 people crammed into the stadium to go wild.

Perhaps the most famous line in the history of boxing was coined in the aftermath by the leading sportswriter of the day, Jimmy Cannon, who described Louis as “a credit to his race – the human race.”

The victory propelled Louis to fame and celebrity, though he was studious in not displaying any of the defiance or controversy that typified the career of his black predecessor Jack Johnson.

He knew his role and performed it to the letter, serving in the forces in World War II, in which his fame was exploited by the government in the war effort. He ended up broke as a greeter in a Las Vegas casino in his twilight years and died in 1981.

Schmeling donated money to pay for the funeral and also acted as a pallbearer, testimony to the respect and friendship both men went on to enjoy after sharing the ring together.

Schmeling returned to Germany after the fight to find his status had plummeted. The Nazis no longer treated him as a national hero or symbol of Aryan manhood – no great disappointment to the reluctant Schmeling. Indeed, the German champion provided sanctuary to two Jewish boys later the same year during the Kristallnacht pogrom against the Jews. After the war, during which he was conscripted to serve as a paratrooper, Schmeling embarked on a career in business. He died in 2005 just shy of his 100th birthday.

Louis, as with Mohammed Ali in later years, was more than just a boxer to his people. He was a symbol of pride, strength and dignity in the face of the oppression they suffered in the land of the free. Martin Luther King later described what Louis meant to them when he wrote about the execution of a young black prisoner in a southern prison. As the poison gas pellets were dropped in the death chamber and the gas swirled upwards, his last words were: “Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis…”

Reposted from MorningStar.

Warning these are the only sites authorized to sell my art:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/kmencher

https://www.kenney-mencher.net/

http://kenney-mencher.com/

The size is a standard US frame size and can be framed inexpensively.

(Buy framing kits on the US version of Etsy, Amazon or go to DickBlick. (.com's)

I was born in Brooklyn February of 1965. During much of my childhood I lived in Brooklyn, the Bronx, upstate NY, Sarasota, Florida and Manhattan. (Both my mother and father divorced and remarried.) The real hero of my childhood is my older brother Marc who literally changed my diapers, acted as my protector and as my role model.

I started to learn to paint and draw when I was six or seven years old and was convinced that I would be an artist from that age on.

As a teen at the High School of Art and Design I got my best training in Irwin Greenberg’s class where he taught me how to draw, oil paint and watercolor. I also attended classes at the Cooper Union and Art Students League.

My parents threw me out in my senior year of high school, so I earned my GED and worked construction on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was a rough time but my older brother and his partner Kirk rescued me by inviting me to move with them to Cincinnati, Ohio to live and study. While a college student, I worked in restaurants and painted as much as I could. After a year at the University of Cincinnati, I went back to the Bronx where I finished college at CUNY Lehman. Lehman is a fantastic college.

After completing my undergraduate studies, I lived in California and then Ohio completing my two masters’ degrees in Art History and Studio Art. After school I was lucky enough to have dual careers as an exhibiting artist and tenured professor.

In 2014 I began to work on paintings with a strong homoerotic content. Despite excellent sales and well received shows, the galleries I worked with wouldn’t show my new queer work, so I’ve been successfully working mainly directly with my collectors. This change has freed me and allowed me to focus on themes and subjects that, in the past, were rejected or resulted in censorship.

Things are going great! In 2016, after eighteen years of teaching art history and studio courses, I resigned a tenured professorship to pursue painting full time.

EDUCATION

1993-1995 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

MFA Painting

1991-1994 University of California, Davis, CA

MA Art History

1988-1991 City University of New York, Bronx, NY

Magna Cum Laude; BA Art History

1988 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

1981-1985 Art Students' League, Manhattan, NY

1978-1982 Art & Design High School, Manhattan, NY

EMPLOYMENT

1999-2016 Associate Professor of Art & Art History, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

1998-1999 Instructor of Art History & Western Civilization, San Francisco University High School

1996-1998 Assistant Professor of Art & Art History, Texas A&M University, Laredo, TX

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2021 Lone Star Saloon, San Francisco, CA

It’s All About the Bears

2016 Tracy Center for the Arts, Tracy, CA

The Convict and the Boy, A Graphic Novel and Installation by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Art Museum of Los Gatos, Los Gatos, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2008 Sequential Art Gallery, Portland, OR

Cads and Coquettes

2008 Varnish Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

Lovers and Liars

2007 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Faces and Farces

2007 Gallery 2611, Redwood City, CA

Clichés and Characters

2006 Klaudia Marr Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

Kenney Mencher: Recent Work

2006 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Apperceptions and Allegories

2006 Norton Studio Gallery, Pacific Art League, Palo Alto, CA

Being There

2006 Esteban Sabar Gallery, Oakland, CA

Similes and Sayings

2005 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Hamlettes on Wry

2005 Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts, Mountain View, CA

2004 Louie-Meager Art Gallery, Gary Soren Smith Center, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Dress Code

2004 STRS Gallery, Sacramento, CA

1997 Laredo Center for the Arts, Laredo, TX

Noir Images (Solo Show)

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

The Men's Room

2010 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Go Figure

2010 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Resurgence

2009 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

In Black and White: Monochromatic Paintings by Kenney Mencher and Caroline Meyer

2008 Art Museum of Los Gatos, CA

Sex, Politics and Misogyny, Peter Langenbach and Kenney Mencher

2006-07 Klaudia Marr, Santa Fe, NM

14th Annual Realism Invitational

13th Annual Realism Invitational

2006 Triton Art Museum, Santa Clara, CA

Beyond the Likeness: Self Portraits by California Artists

2003 Hang Gallery Palo Alto, CA

One More Thing Before I Go

1999 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

First Annual Realism Invitational

2001 Craighead-Green, Dallas, TX

Kenney Mencher and Connie Connally

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Small Works

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Nancy Switzer, Milt Kobayashi, and Kenney Mencher

Add To Cart

FREE SHIPPING

THIS WORK IS ORIGINAL (NOT A PRINT OR GICLEE)

Shipping takes 3-4 Weeks

Joseph Louis Barrow was an American professional boxer who competed from 1934 to 1951. Nicknamed the Brown Bomber, Louis is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential boxers of all time. He reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1937 until his temporary retirement in 1949

Quotes from Joe Louis

“Every man's got to figure to get beat sometime.” “I don't like money, actually, but it quiets my nerves.” “Everybody wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die.” ” Once that bell rings you're on your own.

How Joe Louis became a symbol of the fight against racism

June 27, 2014 12:37 PM CDT BY JOHN WIGHT

On June 19, 1936 the Brown Bomber Joe Louis climbed through the ropes at the Yankee Stadium in New York to face German heavyweight contender Max Schmeling in front of a sell-out crowd to contest a non-title bout scheduled for 15 rounds.

Louis was just 22 when he faced Schmeling for the first time, undefeated in 24 fights. Schmeling had already won and lost the world title and at 30 was felt to be easy pickings for his much younger and more complete opponent, who was already on the way to establishing the legend he was destined to become.

The backdrop: fascism in Europe, lynchings in U.S

The onward march of fascism in Europe was the backdrop to the fight. Adolf Hitler had been in power in Germany for three years, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was intent on reliving the glory days of the Roman empire and Spain was embroiled in a brutal civil war which foreshadowed the cataclysm that was to engulf Europe and the world just a few years later.

Meanwhile, the United States regarded itself as the home of freedom and democracy, even though for young black men like Joe Louis it was closer to hell, with lynchings still a regular occurrence in parts of the south and blacks treated as second-class citizens even in areas without formal segregation.

The fight itself proved that Schmeling’s claim to have identified a flaw in the Brown Bomber’s style was not mere hyperbole. Louis had a habit of lowering his left hand after jabbing with it, which Schmeling aimed to exploit with right hands.

The German dropped Louis to the canvas for the first time in his career with just such a right hand in the fourth round and by the time he finally knocked him out in the 12th he was ahead on all three of the judges’ scorecards.

It was a major upset. In black communities throughout the US Louis’ first defeat was met with huge consternation by people who saw in him their savior and hope.

Maya Angelou wrote: “My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, yet another Black man hanging on a tree. One more woman ambushed and raped. A Black boy whipped and maimed. It was hounds on the trail of a man running through slimy swamps. … If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help.”

Meanwhile, after a personal message from Hitler congratulating him, Schmeling told a German reporter: “At this moment I have to tell Germany, I have to report to the Fuhrer in particular, that the thoughts of all my countrymen were with me in this fight.

“That the Fuhrer and his faithful people were thinking of me. This thought gave me the strength to succeed in this fight. It gave me the courage and the endurance to win this victory for Germany’s colors.”

The second fight: Schmeling and Louis political symbols

By the time of the second fight two years later, the world lay on the brink of war and the Nazis’ terror campaign against communists, socialists, trade unionists, the disabled, gays, Gypsies and Jews was underway.

Schmeling and Louis were now political symbols for their respective countries whether they liked it or not and, as the fight on June 22 1938 approached, again held at New York’s Yankee Stadium, the tension far exceeded any that had been present in the lead-up to the first contest.

Despite his message praising Hitler following the first fight Schmeling was not a member of the Nazi party and always denied Nazi claims of racial superiority.

His wife and mother were prevented from travelling to the US with him to forestall the possibility of them defecting. His entourage included a Nazi official to handle press and publicity.

It was this official who was responsible for issuing the infamous statement that a black man could not defeat Schmeling and that his purse would be used to help pay for more German tanks.

As for Louis, he attended a meeting with President Franklin D Roosevelt at the White House prior to the fight, where he was left in no doubt of the importance of the outcome to the country at large.

The irony was striking

The irony was striking – a young black man whose people were being systematically denied their civil and human rights had become the champion of the country responsible.

Louis was a different fighter to two years earlier. Since losing to the German in 1936 he’d gone on to win the world heavyweight title and successfully defended it three times.

He was 25 and fully in his prime, which told from the opening bell when he went straight on the offensive, unleashing crunching combinations against Schmeling’s body and head.

The German had no answer to the barrage and went down after just 90 seconds. When the action resumed, Louis picked up where he’d left off, again sending his opponent to the canvas.

This time Schmeling’s corner, realizing their man was being taken apart, intervened to call a halt to what by now was a public execution. The fight was over in the first round, causing the 70,000 people crammed into the stadium to go wild.

Perhaps the most famous line in the history of boxing was coined in the aftermath by the leading sportswriter of the day, Jimmy Cannon, who described Louis as “a credit to his race – the human race.”

The victory propelled Louis to fame and celebrity, though he was studious in not displaying any of the defiance or controversy that typified the career of his black predecessor Jack Johnson.

He knew his role and performed it to the letter, serving in the forces in World War II, in which his fame was exploited by the government in the war effort. He ended up broke as a greeter in a Las Vegas casino in his twilight years and died in 1981.

Schmeling donated money to pay for the funeral and also acted as a pallbearer, testimony to the respect and friendship both men went on to enjoy after sharing the ring together.

Schmeling returned to Germany after the fight to find his status had plummeted. The Nazis no longer treated him as a national hero or symbol of Aryan manhood – no great disappointment to the reluctant Schmeling. Indeed, the German champion provided sanctuary to two Jewish boys later the same year during the Kristallnacht pogrom against the Jews. After the war, during which he was conscripted to serve as a paratrooper, Schmeling embarked on a career in business. He died in 2005 just shy of his 100th birthday.

Louis, as with Mohammed Ali in later years, was more than just a boxer to his people. He was a symbol of pride, strength and dignity in the face of the oppression they suffered in the land of the free. Martin Luther King later described what Louis meant to them when he wrote about the execution of a young black prisoner in a southern prison. As the poison gas pellets were dropped in the death chamber and the gas swirled upwards, his last words were: “Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis…”

Reposted from MorningStar.

Warning these are the only sites authorized to sell my art:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/kmencher

https://www.kenney-mencher.net/

http://kenney-mencher.com/

The size is a standard US frame size and can be framed inexpensively.

(Buy framing kits on the US version of Etsy, Amazon or go to DickBlick. (.com's)

I was born in Brooklyn February of 1965. During much of my childhood I lived in Brooklyn, the Bronx, upstate NY, Sarasota, Florida and Manhattan. (Both my mother and father divorced and remarried.) The real hero of my childhood is my older brother Marc who literally changed my diapers, acted as my protector and as my role model.

I started to learn to paint and draw when I was six or seven years old and was convinced that I would be an artist from that age on.

As a teen at the High School of Art and Design I got my best training in Irwin Greenberg’s class where he taught me how to draw, oil paint and watercolor. I also attended classes at the Cooper Union and Art Students League.

My parents threw me out in my senior year of high school, so I earned my GED and worked construction on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was a rough time but my older brother and his partner Kirk rescued me by inviting me to move with them to Cincinnati, Ohio to live and study. While a college student, I worked in restaurants and painted as much as I could. After a year at the University of Cincinnati, I went back to the Bronx where I finished college at CUNY Lehman. Lehman is a fantastic college.

After completing my undergraduate studies, I lived in California and then Ohio completing my two masters’ degrees in Art History and Studio Art. After school I was lucky enough to have dual careers as an exhibiting artist and tenured professor.

In 2014 I began to work on paintings with a strong homoerotic content. Despite excellent sales and well received shows, the galleries I worked with wouldn’t show my new queer work, so I’ve been successfully working mainly directly with my collectors. This change has freed me and allowed me to focus on themes and subjects that, in the past, were rejected or resulted in censorship.

Things are going great! In 2016, after eighteen years of teaching art history and studio courses, I resigned a tenured professorship to pursue painting full time.

EDUCATION

1993-1995 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

MFA Painting

1991-1994 University of California, Davis, CA

MA Art History

1988-1991 City University of New York, Bronx, NY

Magna Cum Laude; BA Art History

1988 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

1981-1985 Art Students' League, Manhattan, NY

1978-1982 Art & Design High School, Manhattan, NY

EMPLOYMENT

1999-2016 Associate Professor of Art & Art History, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

1998-1999 Instructor of Art History & Western Civilization, San Francisco University High School

1996-1998 Assistant Professor of Art & Art History, Texas A&M University, Laredo, TX

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2021 Lone Star Saloon, San Francisco, CA

It’s All About the Bears

2016 Tracy Center for the Arts, Tracy, CA

The Convict and the Boy, A Graphic Novel and Installation by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Art Museum of Los Gatos, Los Gatos, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2008 Sequential Art Gallery, Portland, OR

Cads and Coquettes

2008 Varnish Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

Lovers and Liars

2007 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Faces and Farces

2007 Gallery 2611, Redwood City, CA

Clichés and Characters

2006 Klaudia Marr Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

Kenney Mencher: Recent Work

2006 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Apperceptions and Allegories

2006 Norton Studio Gallery, Pacific Art League, Palo Alto, CA

Being There

2006 Esteban Sabar Gallery, Oakland, CA

Similes and Sayings

2005 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Hamlettes on Wry

2005 Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts, Mountain View, CA

2004 Louie-Meager Art Gallery, Gary Soren Smith Center, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Dress Code

2004 STRS Gallery, Sacramento, CA

1997 Laredo Center for the Arts, Laredo, TX

Noir Images (Solo Show)

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

The Men's Room

2010 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Go Figure

2010 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Resurgence

2009 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

In Black and White: Monochromatic Paintings by Kenney Mencher and Caroline Meyer

2008 Art Museum of Los Gatos, CA

Sex, Politics and Misogyny, Peter Langenbach and Kenney Mencher

2006-07 Klaudia Marr, Santa Fe, NM

14th Annual Realism Invitational

13th Annual Realism Invitational

2006 Triton Art Museum, Santa Clara, CA

Beyond the Likeness: Self Portraits by California Artists

2003 Hang Gallery Palo Alto, CA

One More Thing Before I Go

1999 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

First Annual Realism Invitational

2001 Craighead-Green, Dallas, TX

Kenney Mencher and Connie Connally

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Small Works

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Nancy Switzer, Milt Kobayashi, and Kenney Mencher

THIS WORK IS ORIGINAL (NOT A PRINT OR GICLEE)

Shipping takes 3-4 Weeks

Joseph Louis Barrow was an American professional boxer who competed from 1934 to 1951. Nicknamed the Brown Bomber, Louis is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential boxers of all time. He reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1937 until his temporary retirement in 1949

Quotes from Joe Louis

“Every man's got to figure to get beat sometime.” “I don't like money, actually, but it quiets my nerves.” “Everybody wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die.” ” Once that bell rings you're on your own.

How Joe Louis became a symbol of the fight against racism

June 27, 2014 12:37 PM CDT BY JOHN WIGHT

On June 19, 1936 the Brown Bomber Joe Louis climbed through the ropes at the Yankee Stadium in New York to face German heavyweight contender Max Schmeling in front of a sell-out crowd to contest a non-title bout scheduled for 15 rounds.

Louis was just 22 when he faced Schmeling for the first time, undefeated in 24 fights. Schmeling had already won and lost the world title and at 30 was felt to be easy pickings for his much younger and more complete opponent, who was already on the way to establishing the legend he was destined to become.

The backdrop: fascism in Europe, lynchings in U.S

The onward march of fascism in Europe was the backdrop to the fight. Adolf Hitler had been in power in Germany for three years, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was intent on reliving the glory days of the Roman empire and Spain was embroiled in a brutal civil war which foreshadowed the cataclysm that was to engulf Europe and the world just a few years later.

Meanwhile, the United States regarded itself as the home of freedom and democracy, even though for young black men like Joe Louis it was closer to hell, with lynchings still a regular occurrence in parts of the south and blacks treated as second-class citizens even in areas without formal segregation.

The fight itself proved that Schmeling’s claim to have identified a flaw in the Brown Bomber’s style was not mere hyperbole. Louis had a habit of lowering his left hand after jabbing with it, which Schmeling aimed to exploit with right hands.

The German dropped Louis to the canvas for the first time in his career with just such a right hand in the fourth round and by the time he finally knocked him out in the 12th he was ahead on all three of the judges’ scorecards.

It was a major upset. In black communities throughout the US Louis’ first defeat was met with huge consternation by people who saw in him their savior and hope.

Maya Angelou wrote: “My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, yet another Black man hanging on a tree. One more woman ambushed and raped. A Black boy whipped and maimed. It was hounds on the trail of a man running through slimy swamps. … If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help.”

Meanwhile, after a personal message from Hitler congratulating him, Schmeling told a German reporter: “At this moment I have to tell Germany, I have to report to the Fuhrer in particular, that the thoughts of all my countrymen were with me in this fight.

“That the Fuhrer and his faithful people were thinking of me. This thought gave me the strength to succeed in this fight. It gave me the courage and the endurance to win this victory for Germany’s colors.”

The second fight: Schmeling and Louis political symbols

By the time of the second fight two years later, the world lay on the brink of war and the Nazis’ terror campaign against communists, socialists, trade unionists, the disabled, gays, Gypsies and Jews was underway.

Schmeling and Louis were now political symbols for their respective countries whether they liked it or not and, as the fight on June 22 1938 approached, again held at New York’s Yankee Stadium, the tension far exceeded any that had been present in the lead-up to the first contest.

Despite his message praising Hitler following the first fight Schmeling was not a member of the Nazi party and always denied Nazi claims of racial superiority.

His wife and mother were prevented from travelling to the US with him to forestall the possibility of them defecting. His entourage included a Nazi official to handle press and publicity.

It was this official who was responsible for issuing the infamous statement that a black man could not defeat Schmeling and that his purse would be used to help pay for more German tanks.

As for Louis, he attended a meeting with President Franklin D Roosevelt at the White House prior to the fight, where he was left in no doubt of the importance of the outcome to the country at large.

The irony was striking

The irony was striking – a young black man whose people were being systematically denied their civil and human rights had become the champion of the country responsible.

Louis was a different fighter to two years earlier. Since losing to the German in 1936 he’d gone on to win the world heavyweight title and successfully defended it three times.

He was 25 and fully in his prime, which told from the opening bell when he went straight on the offensive, unleashing crunching combinations against Schmeling’s body and head.

The German had no answer to the barrage and went down after just 90 seconds. When the action resumed, Louis picked up where he’d left off, again sending his opponent to the canvas.

This time Schmeling’s corner, realizing their man was being taken apart, intervened to call a halt to what by now was a public execution. The fight was over in the first round, causing the 70,000 people crammed into the stadium to go wild.

Perhaps the most famous line in the history of boxing was coined in the aftermath by the leading sportswriter of the day, Jimmy Cannon, who described Louis as “a credit to his race – the human race.”

The victory propelled Louis to fame and celebrity, though he was studious in not displaying any of the defiance or controversy that typified the career of his black predecessor Jack Johnson.

He knew his role and performed it to the letter, serving in the forces in World War II, in which his fame was exploited by the government in the war effort. He ended up broke as a greeter in a Las Vegas casino in his twilight years and died in 1981.

Schmeling donated money to pay for the funeral and also acted as a pallbearer, testimony to the respect and friendship both men went on to enjoy after sharing the ring together.

Schmeling returned to Germany after the fight to find his status had plummeted. The Nazis no longer treated him as a national hero or symbol of Aryan manhood – no great disappointment to the reluctant Schmeling. Indeed, the German champion provided sanctuary to two Jewish boys later the same year during the Kristallnacht pogrom against the Jews. After the war, during which he was conscripted to serve as a paratrooper, Schmeling embarked on a career in business. He died in 2005 just shy of his 100th birthday.

Louis, as with Mohammed Ali in later years, was more than just a boxer to his people. He was a symbol of pride, strength and dignity in the face of the oppression they suffered in the land of the free. Martin Luther King later described what Louis meant to them when he wrote about the execution of a young black prisoner in a southern prison. As the poison gas pellets were dropped in the death chamber and the gas swirled upwards, his last words were: “Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis…”

Reposted from MorningStar.

Warning these are the only sites authorized to sell my art:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/kmencher

https://www.kenney-mencher.net/

http://kenney-mencher.com/

The size is a standard US frame size and can be framed inexpensively.

(Buy framing kits on the US version of Etsy, Amazon or go to DickBlick. (.com's)

I was born in Brooklyn February of 1965. During much of my childhood I lived in Brooklyn, the Bronx, upstate NY, Sarasota, Florida and Manhattan. (Both my mother and father divorced and remarried.) The real hero of my childhood is my older brother Marc who literally changed my diapers, acted as my protector and as my role model.

I started to learn to paint and draw when I was six or seven years old and was convinced that I would be an artist from that age on.

As a teen at the High School of Art and Design I got my best training in Irwin Greenberg’s class where he taught me how to draw, oil paint and watercolor. I also attended classes at the Cooper Union and Art Students League.

My parents threw me out in my senior year of high school, so I earned my GED and worked construction on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was a rough time but my older brother and his partner Kirk rescued me by inviting me to move with them to Cincinnati, Ohio to live and study. While a college student, I worked in restaurants and painted as much as I could. After a year at the University of Cincinnati, I went back to the Bronx where I finished college at CUNY Lehman. Lehman is a fantastic college.

After completing my undergraduate studies, I lived in California and then Ohio completing my two masters’ degrees in Art History and Studio Art. After school I was lucky enough to have dual careers as an exhibiting artist and tenured professor.

In 2014 I began to work on paintings with a strong homoerotic content. Despite excellent sales and well received shows, the galleries I worked with wouldn’t show my new queer work, so I’ve been successfully working mainly directly with my collectors. This change has freed me and allowed me to focus on themes and subjects that, in the past, were rejected or resulted in censorship.

Things are going great! In 2016, after eighteen years of teaching art history and studio courses, I resigned a tenured professorship to pursue painting full time.

EDUCATION

1993-1995 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

MFA Painting

1991-1994 University of California, Davis, CA

MA Art History

1988-1991 City University of New York, Bronx, NY

Magna Cum Laude; BA Art History

1988 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

1981-1985 Art Students' League, Manhattan, NY

1978-1982 Art & Design High School, Manhattan, NY

EMPLOYMENT

1999-2016 Associate Professor of Art & Art History, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

1998-1999 Instructor of Art History & Western Civilization, San Francisco University High School

1996-1998 Assistant Professor of Art & Art History, Texas A&M University, Laredo, TX

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2021 Lone Star Saloon, San Francisco, CA

It’s All About the Bears

2016 Tracy Center for the Arts, Tracy, CA

The Convict and the Boy, A Graphic Novel and Installation by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Art Museum of Los Gatos, Los Gatos, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2008 Sequential Art Gallery, Portland, OR

Cads and Coquettes

2008 Varnish Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

Lovers and Liars

2007 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Faces and Farces

2007 Gallery 2611, Redwood City, CA

Clichés and Characters

2006 Klaudia Marr Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

Kenney Mencher: Recent Work

2006 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Apperceptions and Allegories

2006 Norton Studio Gallery, Pacific Art League, Palo Alto, CA

Being There

2006 Esteban Sabar Gallery, Oakland, CA

Similes and Sayings

2005 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Hamlettes on Wry

2005 Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts, Mountain View, CA

2004 Louie-Meager Art Gallery, Gary Soren Smith Center, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Dress Code

2004 STRS Gallery, Sacramento, CA

1997 Laredo Center for the Arts, Laredo, TX

Noir Images (Solo Show)

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

The Men's Room

2010 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Go Figure

2010 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Resurgence

2009 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

In Black and White: Monochromatic Paintings by Kenney Mencher and Caroline Meyer

2008 Art Museum of Los Gatos, CA

Sex, Politics and Misogyny, Peter Langenbach and Kenney Mencher

2006-07 Klaudia Marr, Santa Fe, NM

14th Annual Realism Invitational

13th Annual Realism Invitational

2006 Triton Art Museum, Santa Clara, CA

Beyond the Likeness: Self Portraits by California Artists

2003 Hang Gallery Palo Alto, CA

One More Thing Before I Go

1999 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

First Annual Realism Invitational

2001 Craighead-Green, Dallas, TX

Kenney Mencher and Connie Connally

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Small Works

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Nancy Switzer, Milt Kobayashi, and Kenney Mencher

FREE SHIPPING

THIS WORK IS ORIGINAL (NOT A PRINT OR GICLEE)

Shipping takes 3-4 Weeks

Joseph Louis Barrow was an American professional boxer who competed from 1934 to 1951. Nicknamed the Brown Bomber, Louis is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential boxers of all time. He reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1937 until his temporary retirement in 1949

Quotes from Joe Louis

“Every man's got to figure to get beat sometime.” “I don't like money, actually, but it quiets my nerves.” “Everybody wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die.” ” Once that bell rings you're on your own.

How Joe Louis became a symbol of the fight against racism

June 27, 2014 12:37 PM CDT BY JOHN WIGHT

On June 19, 1936 the Brown Bomber Joe Louis climbed through the ropes at the Yankee Stadium in New York to face German heavyweight contender Max Schmeling in front of a sell-out crowd to contest a non-title bout scheduled for 15 rounds.

Louis was just 22 when he faced Schmeling for the first time, undefeated in 24 fights. Schmeling had already won and lost the world title and at 30 was felt to be easy pickings for his much younger and more complete opponent, who was already on the way to establishing the legend he was destined to become.

The backdrop: fascism in Europe, lynchings in U.S

The onward march of fascism in Europe was the backdrop to the fight. Adolf Hitler had been in power in Germany for three years, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was intent on reliving the glory days of the Roman empire and Spain was embroiled in a brutal civil war which foreshadowed the cataclysm that was to engulf Europe and the world just a few years later.

Meanwhile, the United States regarded itself as the home of freedom and democracy, even though for young black men like Joe Louis it was closer to hell, with lynchings still a regular occurrence in parts of the south and blacks treated as second-class citizens even in areas without formal segregation.

The fight itself proved that Schmeling’s claim to have identified a flaw in the Brown Bomber’s style was not mere hyperbole. Louis had a habit of lowering his left hand after jabbing with it, which Schmeling aimed to exploit with right hands.

The German dropped Louis to the canvas for the first time in his career with just such a right hand in the fourth round and by the time he finally knocked him out in the 12th he was ahead on all three of the judges’ scorecards.

It was a major upset. In black communities throughout the US Louis’ first defeat was met with huge consternation by people who saw in him their savior and hope.

Maya Angelou wrote: “My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, yet another Black man hanging on a tree. One more woman ambushed and raped. A Black boy whipped and maimed. It was hounds on the trail of a man running through slimy swamps. … If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help.”

Meanwhile, after a personal message from Hitler congratulating him, Schmeling told a German reporter: “At this moment I have to tell Germany, I have to report to the Fuhrer in particular, that the thoughts of all my countrymen were with me in this fight.

“That the Fuhrer and his faithful people were thinking of me. This thought gave me the strength to succeed in this fight. It gave me the courage and the endurance to win this victory for Germany’s colors.”

The second fight: Schmeling and Louis political symbols

By the time of the second fight two years later, the world lay on the brink of war and the Nazis’ terror campaign against communists, socialists, trade unionists, the disabled, gays, Gypsies and Jews was underway.

Schmeling and Louis were now political symbols for their respective countries whether they liked it or not and, as the fight on June 22 1938 approached, again held at New York’s Yankee Stadium, the tension far exceeded any that had been present in the lead-up to the first contest.

Despite his message praising Hitler following the first fight Schmeling was not a member of the Nazi party and always denied Nazi claims of racial superiority.

His wife and mother were prevented from travelling to the US with him to forestall the possibility of them defecting. His entourage included a Nazi official to handle press and publicity.

It was this official who was responsible for issuing the infamous statement that a black man could not defeat Schmeling and that his purse would be used to help pay for more German tanks.

As for Louis, he attended a meeting with President Franklin D Roosevelt at the White House prior to the fight, where he was left in no doubt of the importance of the outcome to the country at large.

The irony was striking

The irony was striking – a young black man whose people were being systematically denied their civil and human rights had become the champion of the country responsible.

Louis was a different fighter to two years earlier. Since losing to the German in 1936 he’d gone on to win the world heavyweight title and successfully defended it three times.

He was 25 and fully in his prime, which told from the opening bell when he went straight on the offensive, unleashing crunching combinations against Schmeling’s body and head.

The German had no answer to the barrage and went down after just 90 seconds. When the action resumed, Louis picked up where he’d left off, again sending his opponent to the canvas.

This time Schmeling’s corner, realizing their man was being taken apart, intervened to call a halt to what by now was a public execution. The fight was over in the first round, causing the 70,000 people crammed into the stadium to go wild.

Perhaps the most famous line in the history of boxing was coined in the aftermath by the leading sportswriter of the day, Jimmy Cannon, who described Louis as “a credit to his race – the human race.”

The victory propelled Louis to fame and celebrity, though he was studious in not displaying any of the defiance or controversy that typified the career of his black predecessor Jack Johnson.

He knew his role and performed it to the letter, serving in the forces in World War II, in which his fame was exploited by the government in the war effort. He ended up broke as a greeter in a Las Vegas casino in his twilight years and died in 1981.

Schmeling donated money to pay for the funeral and also acted as a pallbearer, testimony to the respect and friendship both men went on to enjoy after sharing the ring together.

Schmeling returned to Germany after the fight to find his status had plummeted. The Nazis no longer treated him as a national hero or symbol of Aryan manhood – no great disappointment to the reluctant Schmeling. Indeed, the German champion provided sanctuary to two Jewish boys later the same year during the Kristallnacht pogrom against the Jews. After the war, during which he was conscripted to serve as a paratrooper, Schmeling embarked on a career in business. He died in 2005 just shy of his 100th birthday.

Louis, as with Mohammed Ali in later years, was more than just a boxer to his people. He was a symbol of pride, strength and dignity in the face of the oppression they suffered in the land of the free. Martin Luther King later described what Louis meant to them when he wrote about the execution of a young black prisoner in a southern prison. As the poison gas pellets were dropped in the death chamber and the gas swirled upwards, his last words were: “Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis…”

Reposted from MorningStar.

Warning these are the only sites authorized to sell my art:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/kmencher

https://www.kenney-mencher.net/

http://kenney-mencher.com/

The size is a standard US frame size and can be framed inexpensively.

(Buy framing kits on the US version of Etsy, Amazon or go to DickBlick. (.com's)

I was born in Brooklyn February of 1965. During much of my childhood I lived in Brooklyn, the Bronx, upstate NY, Sarasota, Florida and Manhattan. (Both my mother and father divorced and remarried.) The real hero of my childhood is my older brother Marc who literally changed my diapers, acted as my protector and as my role model.

I started to learn to paint and draw when I was six or seven years old and was convinced that I would be an artist from that age on.

As a teen at the High School of Art and Design I got my best training in Irwin Greenberg’s class where he taught me how to draw, oil paint and watercolor. I also attended classes at the Cooper Union and Art Students League.

My parents threw me out in my senior year of high school, so I earned my GED and worked construction on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was a rough time but my older brother and his partner Kirk rescued me by inviting me to move with them to Cincinnati, Ohio to live and study. While a college student, I worked in restaurants and painted as much as I could. After a year at the University of Cincinnati, I went back to the Bronx where I finished college at CUNY Lehman. Lehman is a fantastic college.

After completing my undergraduate studies, I lived in California and then Ohio completing my two masters’ degrees in Art History and Studio Art. After school I was lucky enough to have dual careers as an exhibiting artist and tenured professor.

In 2014 I began to work on paintings with a strong homoerotic content. Despite excellent sales and well received shows, the galleries I worked with wouldn’t show my new queer work, so I’ve been successfully working mainly directly with my collectors. This change has freed me and allowed me to focus on themes and subjects that, in the past, were rejected or resulted in censorship.

Things are going great! In 2016, after eighteen years of teaching art history and studio courses, I resigned a tenured professorship to pursue painting full time.

EDUCATION

1993-1995 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

MFA Painting

1991-1994 University of California, Davis, CA

MA Art History

1988-1991 City University of New York, Bronx, NY

Magna Cum Laude; BA Art History

1988 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

1981-1985 Art Students' League, Manhattan, NY

1978-1982 Art & Design High School, Manhattan, NY

EMPLOYMENT

1999-2016 Associate Professor of Art & Art History, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

1998-1999 Instructor of Art History & Western Civilization, San Francisco University High School

1996-1998 Assistant Professor of Art & Art History, Texas A&M University, Laredo, TX

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2021 Lone Star Saloon, San Francisco, CA

It’s All About the Bears

2016 Tracy Center for the Arts, Tracy, CA

The Convict and the Boy, A Graphic Novel and Installation by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2012 Art Museum of Los Gatos, Los Gatos, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Renovated Reputations: Paintings, Installation and Mixed Media by Kenney Mencher with publication edited by the artist.

2008 Sequential Art Gallery, Portland, OR

Cads and Coquettes

2008 Varnish Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

Lovers and Liars

2007 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Faces and Farces

2007 Gallery 2611, Redwood City, CA

Clichés and Characters

2006 Klaudia Marr Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

Kenney Mencher: Recent Work

2006 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Apperceptions and Allegories

2006 Norton Studio Gallery, Pacific Art League, Palo Alto, CA

Being There

2006 Esteban Sabar Gallery, Oakland, CA

Similes and Sayings

2005 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Hamlettes on Wry

2005 Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts, Mountain View, CA

2004 Louie-Meager Art Gallery, Gary Soren Smith Center, Ohlone College, Fremont, CA

Dress Code

2004 STRS Gallery, Sacramento, CA

1997 Laredo Center for the Arts, Laredo, TX

Noir Images (Solo Show)

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2011 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

The Men's Room

2010 Elliott Fouts Gallery, Sacramento, CA

Go Figure

2010 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Resurgence

2009 ArtHaus Gallery, San Francisco, CA

In Black and White: Monochromatic Paintings by Kenney Mencher and Caroline Meyer

2008 Art Museum of Los Gatos, CA

Sex, Politics and Misogyny, Peter Langenbach and Kenney Mencher

2006-07 Klaudia Marr, Santa Fe, NM

14th Annual Realism Invitational

13th Annual Realism Invitational

2006 Triton Art Museum, Santa Clara, CA

Beyond the Likeness: Self Portraits by California Artists

2003 Hang Gallery Palo Alto, CA

One More Thing Before I Go

1999 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

First Annual Realism Invitational

2001 Craighead-Green, Dallas, TX

Kenney Mencher and Connie Connally

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Small Works

1998 Jenkins-Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Nancy Switzer, Milt Kobayashi, and Kenney Mencher

THIS WORK IS ORIGINAL (NOT A PRINT OR GICLEE)

Shipping takes 3-4 Weeks

Joseph Louis Barrow was an American professional boxer who competed from 1934 to 1951. Nicknamed the Brown Bomber, Louis is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential boxers of all time. He reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1937 until his temporary retirement in 1949

Quotes from Joe Louis

“Every man's got to figure to get beat sometime.” “I don't like money, actually, but it quiets my nerves.” “Everybody wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die.” ” Once that bell rings you're on your own.

How Joe Louis became a symbol of the fight against racism

June 27, 2014 12:37 PM CDT BY JOHN WIGHT

On June 19, 1936 the Brown Bomber Joe Louis climbed through the ropes at the Yankee Stadium in New York to face German heavyweight contender Max Schmeling in front of a sell-out crowd to contest a non-title bout scheduled for 15 rounds.

Louis was just 22 when he faced Schmeling for the first time, undefeated in 24 fights. Schmeling had already won and lost the world title and at 30 was felt to be easy pickings for his much younger and more complete opponent, who was already on the way to establishing the legend he was destined to become.

The backdrop: fascism in Europe, lynchings in U.S

The onward march of fascism in Europe was the backdrop to the fight. Adolf Hitler had been in power in Germany for three years, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was intent on reliving the glory days of the Roman empire and Spain was embroiled in a brutal civil war which foreshadowed the cataclysm that was to engulf Europe and the world just a few years later.

Meanwhile, the United States regarded itself as the home of freedom and democracy, even though for young black men like Joe Louis it was closer to hell, with lynchings still a regular occurrence in parts of the south and blacks treated as second-class citizens even in areas without formal segregation.

The fight itself proved that Schmeling’s claim to have identified a flaw in the Brown Bomber’s style was not mere hyperbole. Louis had a habit of lowering his left hand after jabbing with it, which Schmeling aimed to exploit with right hands.

The German dropped Louis to the canvas for the first time in his career with just such a right hand in the fourth round and by the time he finally knocked him out in the 12th he was ahead on all three of the judges’ scorecards.

It was a major upset. In black communities throughout the US Louis’ first defeat was met with huge consternation by people who saw in him their savior and hope.

Maya Angelou wrote: “My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, yet another Black man hanging on a tree. One more woman ambushed and raped. A Black boy whipped and maimed. It was hounds on the trail of a man running through slimy swamps. … If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help.”

Meanwhile, after a personal message from Hitler congratulating him, Schmeling told a German reporter: “At this moment I have to tell Germany, I have to report to the Fuhrer in particular, that the thoughts of all my countrymen were with me in this fight.

“That the Fuhrer and his faithful people were thinking of me. This thought gave me the strength to succeed in this fight. It gave me the courage and the endurance to win this victory for Germany’s colors.”

The second fight: Schmeling and Louis political symbols

By the time of the second fight two years later, the world lay on the brink of war and the Nazis’ terror campaign against communists, socialists, trade unionists, the disabled, gays, Gypsies and Jews was underway.

Schmeling and Louis were now political symbols for their respective countries whether they liked it or not and, as the fight on June 22 1938 approached, again held at New York’s Yankee Stadium, the tension far exceeded any that had been present in the lead-up to the first contest.

Despite his message praising Hitler following the first fight Schmeling was not a member of the Nazi party and always denied Nazi claims of racial superiority.

His wife and mother were prevented from travelling to the US with him to forestall the possibility of them defecting. His entourage included a Nazi official to handle press and publicity.

It was this official who was responsible for issuing the infamous statement that a black man could not defeat Schmeling and that his purse would be used to help pay for more German tanks.

As for Louis, he attended a meeting with President Franklin D Roosevelt at the White House prior to the fight, where he was left in no doubt of the importance of the outcome to the country at large.

The irony was striking

The irony was striking – a young black man whose people were being systematically denied their civil and human rights had become the champion of the country responsible.

Louis was a different fighter to two years earlier. Since losing to the German in 1936 he’d gone on to win the world heavyweight title and successfully defended it three times.

He was 25 and fully in his prime, which told from the opening bell when he went straight on the offensive, unleashing crunching combinations against Schmeling’s body and head.

The German had no answer to the barrage and went down after just 90 seconds. When the action resumed, Louis picked up where he’d left off, again sending his opponent to the canvas.

This time Schmeling’s corner, realizing their man was being taken apart, intervened to call a halt to what by now was a public execution. The fight was over in the first round, causing the 70,000 people crammed into the stadium to go wild.

Perhaps the most famous line in the history of boxing was coined in the aftermath by the leading sportswriter of the day, Jimmy Cannon, who described Louis as “a credit to his race – the human race.”

The victory propelled Louis to fame and celebrity, though he was studious in not displaying any of the defiance or controversy that typified the career of his black predecessor Jack Johnson.

He knew his role and performed it to the letter, serving in the forces in World War II, in which his fame was exploited by the government in the war effort. He ended up broke as a greeter in a Las Vegas casino in his twilight years and died in 1981.

Schmeling donated money to pay for the funeral and also acted as a pallbearer, testimony to the respect and friendship both men went on to enjoy after sharing the ring together.

Schmeling returned to Germany after the fight to find his status had plummeted. The Nazis no longer treated him as a national hero or symbol of Aryan manhood – no great disappointment to the reluctant Schmeling. Indeed, the German champion provided sanctuary to two Jewish boys later the same year during the Kristallnacht pogrom against the Jews. After the war, during which he was conscripted to serve as a paratrooper, Schmeling embarked on a career in business. He died in 2005 just shy of his 100th birthday.

Louis, as with Mohammed Ali in later years, was more than just a boxer to his people. He was a symbol of pride, strength and dignity in the face of the oppression they suffered in the land of the free. Martin Luther King later described what Louis meant to them when he wrote about the execution of a young black prisoner in a southern prison. As the poison gas pellets were dropped in the death chamber and the gas swirled upwards, his last words were: “Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis…”

Reposted from MorningStar.

Warning these are the only sites authorized to sell my art:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/kmencher

https://www.kenney-mencher.net/

http://kenney-mencher.com/

The size is a standard US frame size and can be framed inexpensively.

(Buy framing kits on the US version of Etsy, Amazon or go to DickBlick. (.com's)

I was born in Brooklyn February of 1965. During much of my childhood I lived in Brooklyn, the Bronx, upstate NY, Sarasota, Florida and Manhattan. (Both my mother and father divorced and remarried.) The real hero of my childhood is my older brother Marc who literally changed my diapers, acted as my protector and as my role model.

I started to learn to paint and draw when I was six or seven years old and was convinced that I would be an artist from that age on.

As a teen at the High School of Art and Design I got my best training in Irwin Greenberg’s class where he taught me how to draw, oil paint and watercolor. I also attended classes at the Cooper Union and Art Students League.